is the extent to which an operational definition measures what it is intended to measure

- Research article

- Open up Access

- Published:

Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework

BMC Health Services Research volume 17, Article number:88 (2017) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

It is increasingly acknowledged that 'acceptability' should be considered when designing, evaluating and implementing healthcare interventions. However, the published literature offers piddling guidance on how to define or appraise acceptability. The purpose of this study was to develop a multi-construct theoretical framework of acceptability of healthcare interventions that can be applied to assess prospective (i.due east. anticipated) and retrospective (i.due east. experienced) acceptability from the perspective of intervention delivers and recipients.

Methods

Two methods were used to select the component constructs of acceptability. 1) An overview of reviews was conducted to identify systematic reviews that claim to define, theorise or measure acceptability of healthcare interventions. 2) Principles of inductive and deductive reasoning were applied to theorise the concept of acceptability and develop a theoretical framework. Steps included (1) defining acceptability; (2) describing its properties and scope and (3) identifying component constructs and empirical indicators.

Results

From the 43 reviews included in the overview, none explicitly theorised or defined acceptability. Measures used to assess acceptability focused on behaviour (due east.g. dropout rates) (23 reviews), affect (i.e. feelings) (5 reviews), cognition (i.east. perceptions) (seven reviews) or a combination of these (8 reviews).

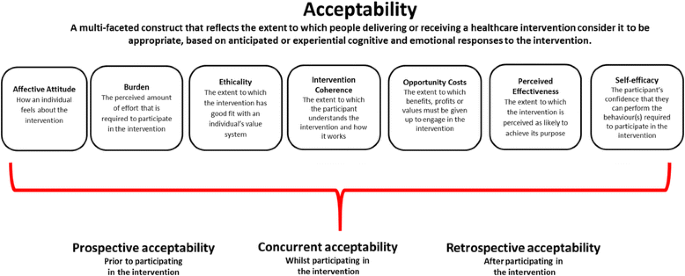

From the methods described above we propose a definition: Acceptability is a multi-faceted construct that reflects the extent to which people delivering or receiving a healthcare intervention consider it to be appropriate, based on anticipated or experienced cerebral and emotional responses to the intervention. The theoretical framework of acceptability (TFA) consists of seven component constructs: affective mental attitude, burden, perceived effectiveness, ethicality, intervention coherence, opportunity costs, and self-efficacy.

Decision

Despite frequent claims that healthcare interventions have assessed acceptability, it is evident that acceptability research could exist more robust. The proposed definition of acceptability and the TFA can inform assessment tools and evaluations of the acceptability of new or existing interventions.

Background

Acceptability has become a fundamental consideration in the design, evaluation and implementation of healthcare interventions. Many healthcare interventions are complex in nature; for case, they can consist of several interacting components, or may be delivered at different levels within a healthcare arrangement [ane]. Intervention developers are faced with the challenge of designing effective healthcare interventions to guarantee the best clinical outcomes achievable with the resources bachelor [2, 3]. Acceptability is a necessary but not sufficient condition for effectiveness of an intervention. Successful implementation depends on the acceptability of the intervention to both intervention deliverers (e.g. patients, researchers or healthcare professionals) and recipients (due east.g. patients or healthcare professionals) [4, 5]. From the patient'southward perspective, the content, context and quality of care received may all accept implications for acceptability. If an intervention is considered adequate, patients are more than likely to adhere to treatment recommendations and to do good from improved clinical outcomes [half dozen, 7]. From the perspective of healthcare professionals, if the commitment of a particular intervention to patients is considered to have low acceptability, the intervention may not be delivered as intended (past intervention designers), which may have an touch on the overall effectiveness of the intervention [8, nine].

In the Britain, the Medical Research Council (MRC) has published 3 guidance documents for researchers and research funders in relation to advisable methods for designing and evaluating circuitous interventions [ten–12]. The number of references to acceptability has increased with each guidance publication which reflects the growing importance of this construct. The 2000 MRC guidance document makes no reference to acceptability, whereas the 2015 guidance refers to acceptability fourteen times but lacks a definition and fails to provide clear instructions on how to assess acceptability.

The 2015 guidance focuses on conducting procedure evaluations of complex interventions. It offers examples of how patients' acceptability may be assessed quantitatively, past administering measures of acceptability or satisfaction, and qualitatively, by asking probing questions focused on agreement how they are interacting with the intervention [12]. Notwithstanding, information technology fails to offer a definition of acceptability or specific materials for operationalising information technology. Without a shared agreement of what acceptability refers to it is unclear how intervention developers are to appraise acceptability for those receiving and delivering healthcare interventions.

Attempts to define acceptability

Defining acceptability is non a straightforward matter. Definitions within the healthcare literature vary considerably highlighting the ambiguity of the concept. Specific examples of definitions include the terms 'handling acceptability' [xiii–15] and 'social acceptability' [sixteen–xviii]. These terms point that acceptability tin be considered from an individual perspective but may also reverberate a more collectively shared judgement nearly the nature of an intervention.

Stainszewska and colleagues (2010) argue that social acceptability refers to "patients' assessment of the acceptability, suitability, capability or effectiveness of intendance and treatment" ([eighteen], p.312). However, this definition is partly circular as information technology states that social acceptability entails acceptability. These authors also omit any guidance on how to measure out patients' cess of intendance and treatment.

Sidani et al., (2009) propose that treatment acceptability is dependent on patients' attitude towards treatment options and their sentence of perceived acceptability prior to participating in an intervention. Factors that influence patients' perceived acceptability include the intervention's "appropriateness in addressing the clinical trouble, suitability to private life style, convenience and effectiveness in managing the clinical problem" ([14], p.421). Whilst this conceptualisation of handling acceptability tin account for patients' decisions in terms of wishing to consummate treatments and willingness to participate in an intervention, it implies a static evaluation of acceptability. Others argue that perceptions of acceptability may change with actual experience of the intervention [19]. For case, the process of participating in an intervention, the content of the intervention, and the perceived or actual effectiveness of the intervention, are likely to influence patients' perceptions of acceptability.

Theorising acceptability

The inconsistency in defining concepts can impede the development of valid assessment instruments [20]. Theorising the concept of acceptability would provide the foundations needed to develop cess tools of acceptability.

Within the disciplines of health psychology, health services research and implementation science the application of theory is recognised as enhancing the development, evaluation and implementation of circuitous interventions [ten, 11, 21–25]. Rimer and Glanz (2005) explain "a theory presents a systematic fashion of understanding events or situations. It is a set of concepts, definitions, and propositions that explain or predict these events or situations by illustrating the relationship betwixt variables" ([26] p.4).

Nosotros debate that theorising the construct of acceptability volition lead to a amend agreement of: (1) what acceptability is (or is proposed to be) (specifically whether acceptability is a unitary or multi-component construct); (two) if acceptability is a multi-component construct, what its components are (or are proposed to be); (three) how acceptability as a construct is proposed to chronicle to other factors, such every bit intervention engagement or adherence; and (4) how it can exist measured.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this commodity is to describe the anterior (empirical) and deductive (theoretical) methods applied to develop a comprehensive theoretical framework of acceptability. This is presented in two sequential studies. The objective of the start study was to review current practice and complete an overview of systematic reviews identifying how the acceptability of healthcare interventions has been defined, operationalised and theorised. The objective of the second study was to supplement evidence from report 1 with a deductive approach to suggest component constructs in the theoretical framework of acceptability.

Methods

Report 1: Overview of reviews

Preliminary scoping searches identified no existing systematic review focused solely on the acceptability of healthcare interventions. However, systematic reviews were identified which considered the acceptability of healthcare and non-healthcare interventions aslope other factors such as effectiveness [27] efficacy [28] and tolerability [29]. We therefore decided to conduct an overview of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions that have included a focus on acceptability, alongside other factors (e.g. effectiveness, feasibility).

Search strategy

Systematic Reviews published from May 2000 (the 2000 MRC guidance was published in April 2000) to February 2016 were retrieved through a single systematic literature search conducted in two phases (i.e. the initial stage one search was conducted in February 2014 and this was updated in phase two Feb 2016). At that place were two search strategies applied to both phase 1 and phase 2 searches. The first strategy was practical to the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), based on the appearance of the truncated term "acceptab*" in article titles. The second search involved applying the relevant systematic review filter (Additional file i) to the search engines OVID (Medline, Embase) and EBSCO Host (PsycINFO), and combining the review filter with the appearance of the term "acceptab*" in commodity titles. Past searching for "acceptab*" within the article title only (rather than within the abstruse or text), we as well ensured that just reviews focused on acceptability as a central variable would be identified. Merely reviews published in English were included as the inquiry question specifically considered the word "acceptability"; this word may accept different shades of meaning when translated into other languages, which may in turn affect the definition and measurement issues under investigation.

Screening of citations

Duplicates were removed in Endnote. All abstracts were reviewed by a single researcher (MS) against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). To assess reliability of the screening process, another researcher (MC) independently reviewed 10% of the abstracts. There was 100% agreement on the abstracts included for total text review.

Total text review and data extraction

One researcher (MS) retrieved all full text papers that met the inclusion criteria and extracted data using an extraction form. Two additional researchers (JF and MC) independently reviewed 10% of the included systematic reviews. The researchers extracted data on how acceptability had been defined, whether acceptability had been theorised, and when and how acceptability had been assessed. There were no disagreements in information extraction.

Assessment of quality

No quality cess tool was practical as it is possible that poor quality systematic reviews would include information relevant to addressing the study aims and objectives.

Definitions of acceptability: consensus group exercises

To identify how acceptability has been defined one researcher (MS) extracted definitions from each of the systematic reviews. Where definitions of acceptability were unclear, a reasonable level of inference was used in guild to identify an implicit definition where review authors imply their understanding of acceptability whilst non directly proposing a definition of acceptability (run across results section for example of inferences).

To check reliability of the coding of extracted text reflecting implicit or explicit definitions seven research psychologists (including the three authors) were asked to allocate the extracted text into the post-obit categories: (1) Conceptual Definition (i.e. an abstruse statement of what acceptability is); (2) Operational Definition (i.east. a concrete statement of how acceptability is measured); (3) Uncertain; and (4) No Definition. The consensus group was allowed to select one or more than options that they considered applicable to each definition. All definitions from the included systematic review papers were extracted, tabulated and presented to the group, together with definitions of "conceptual" and "operational". Explanations of these categories are presented in Table 2. One researcher (MS) facilitated a short word at the first of the job to ensure participants understood the "conceptual" and "operational" definitions. The review authors subsequently repeated the same exercise for extracted definitions from the updated stage two search.

Synthesis

No quantitative synthesis was conducted. All extracted information were analysed by applying the thematic synthesis arroyo [xxx].

Study ii: Development of a theoretical framework of acceptability

The methods applied to develop theory are not always described systematically in the healthcare and psychology literature [31]. Broadly, the nearly common approaches are data driven (lesser up/ inductive) and theory driven (top downwards/ deductive) processes [32–34]. The data driven process focuses on observations from empirical data to form theory, whereas the theory driven process works on the premise of applying existing theory in an endeavor to understand data. The process of theorising is enhanced when inductive and deductive processes are combined [35, 36]. To theorise the concept of acceptability, we applied both anterior and deductive processes by taking a similar arroyo described by Hox [33].

Hox proposed that, in order to theorise, researchers must (one) determine on the concept for measurement; (2) ascertain the concept; (3) describe the properties and scope of the concept (and how information technology differs from other concepts); and (4) identify the empirical indicators and subdomains (i.e. constructs) of the concept. We describe below how steps one-4 were applied in developing a theoretical framework of acceptability.

Step one: Concept for measurement

We first agreed on the limits of the construct to be theorised: acceptability of healthcare interventions.

Footstep two: Defining the concept

To ascertain the concept of acceptability we reviewed the results of the overview of reviews, specifically the conceptual and operational definitions identified past both consensus grouping exercises and the variables reported in the behavioural and self-report measures (identified from the included systematic reviews). Qualitatively synthesising these definitions, we proposed the following conceptual definition of acceptability:

A multi-faceted construct that reflects the extent to which people delivering or receiving a healthcare intervention consider it to be advisable, based on anticipated or experienced cognitive and emotional responses to the intervention.

This definition incorporates the component constructs of acceptability (cerebral and emotional responses) and also provides a hypothesis (cognitive and emotional responses are probable to influence behavioural engagement with the intervention). This working definition of acceptability can be operationalised for the purpose of measurement.

Stride three: Describing the properties and telescopic of the concept

Based on the conceptual definition nosotros identified the properties and telescopic of the construct of acceptability using inductive and deductive methods to determine which constructs all-time represented the core empirical indicators of acceptability.

Inductive methods

The application of inductive methods involved reviewing the empirical data that emerged from the overview of reviews. First, variables identified in the consensus group task to define acceptability, and the variables reported in the observed behavioural measures and self-report measures of acceptability, were grouped together according to similarity. Next, we considered what construct label best described each of the variable groupings. For example, the variables of "attitudinal measures", and "attitudes towards the intervention (how patients felt about the intervention)" was assigned the construct label "affective attitude". Figure 1 presents our conceptual definition and component constructs of acceptability, offer examples of the variables they incorporate. This forms our preliminary theoretical framework of acceptability, TFA (v1).

The theoretical framework of acceptability (v1). Notation: In bold font are the labels nosotros assigned to correspond the examples of the variables applied to operationalise and assess acceptability based on the results from the overview (italic font). Note* Addition of the two control constructs emerging deductively from existing theoretical models

Deductive methods

The deductive process was conducted iteratively using the following three steps:

(1) We considered whether the coverage of the preliminary TFA (v1) could usefully be extended by reviewing the identified component constructs of acceptability against our conceptual definition of acceptability and the results of the overview of reviews.

(2) We considered a range of theories and frameworks from the health psychology and behaviour change literatures that take been applied to predict, explicate or alter health related behaviour.

(3) We reviewed the constructs from these theories and frameworks for their applicability to the TFA. Examples of theories and frameworks discussed include the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) [37] (eastward.g. the construct of Perceived Behavioural Control) and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [38] (e.g. the constructs within the Behavior About Capabilities domain). We discussed whether including additional constructs would add value to the framework in assessing acceptability, specifically if the additional constructs could be measured equally cognitive and / or emotional responses to the intervention. The TPB and the TDF focus on behavior about performing a behaviour whereas the TFA reflects a broader set of behavior nigh the value of a healthcare intervention. We ended that at that place was a more relevant theory that provides better fit with the TFA, the Common Sense Model (CSM) of self-regulation of health and disease [37]. The CSM focuses on beliefs well-nigh a wellness threat and coping procedures that might control the threat. This arroyo is thus consequent with the focus of the TFA on acceptability of healthcare interventions. The CSM proposes that, in response to a perceived health threat, individuals spontaneously generate v kinds of cognitive representation of the illness based around identity (i.eastward. associated symptoms), timeline, cause, command/cure, and consequences. Moss-Morris and colleagues [38] distinguished betwixt personal control (i.eastward. the extent to which an private perceives ane is able to control 1's symptoms or cure the disease) and treatment control (i.e. the extent to which the individual believes the treatment will exist effective in curing the disease). The third step in the deductive process resulted in the inclusion of both treatment control and personal control as boosted constructs within the TFA (v1) (Fig. ane). With these additions the framework appeared to include a parsimonious fix of constructs that provided expert coverage of acceptability as defined.

Step 4: Identifying the empirical indicators for the concept'south constructs

Having identified the component constructs of acceptability, we identified or wrote formal operational definitions for each of the constructs within the TFA (v1). This was done to cheque that the constructs were conceptually distinctive. We first searched the psychological literature for definitions. If a clear definition for a construct was non bachelor in the psychological literature, standard English language language dictionaries and other relevant disciplines (e.one thousand. wellness economic literature for a definition of "opportunity costs") were searched. For each construct, a minimum of ii definitions were identified. Extracted definitions for the component constructs were required to be adaptable to refer straight to "the intervention" (see results section for examples). This procedure resulted in revisions to the TFA (v1) and the evolution of the revised TFA (v2).

Results

Study 1: Overview of reviews

Characteristics of included reviews

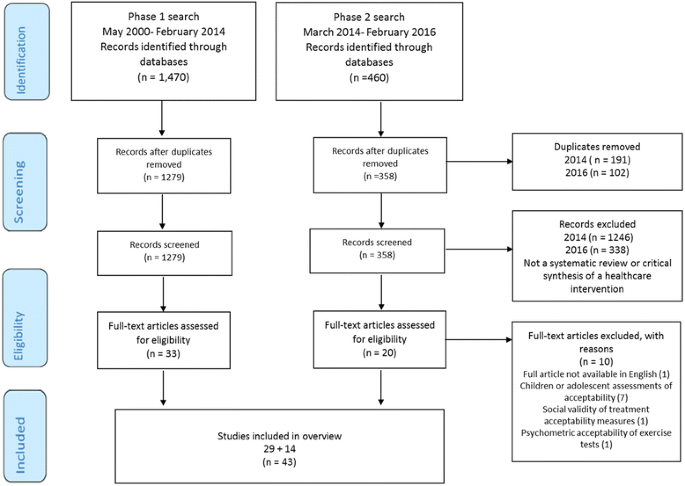

The databases searches identified 1930 references, with 1637 remaining after de-duplication. After screening titles and abstracts, 53 total texts were retrieved for further examination. Of these, x articles were excluded for the following reasons: seven articles focused on children'south and adolescents' acceptability of the intervention, one could non be obtained in English language, 1 article focused on social validity of handling measures in education psychology, and one commodity focused on the psychometric backdrop of exercise tests. Thus, a total of 43 publications were included in this overview (Additional file ii). The breakdown of the search procedure for phase 1 and stage 2 is represented in Fig. 2.

PRISMA diagram of included papers for searches completed in February 2014 and 2016

Assessment of quality

The methodological quality of private studies was assessed in 29 (67%) of the 43 reviews. The Cochrane Tool of Quality Assessment was practical most frequently [39] (eighteen reviews: 62%). Other assessments tools applied included the Jadad Calibration [40] (three reviews: ten%), the Disquisitional Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) guidelines [41] (three reviews: ten%), Espoused guidelines [41] (ii reviews: 6%); Form scale [42] (one review: three%), Effective Public Health Do Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool [43] (one review: 3%) and United States Preventive Services Task Force grading system [44] (1 review: three%).

Assessment of acceptability

Xx-three (55%) reviews assessed acceptability using various objective measures of behaviour as indicators of acceptability: dropout rates, all-cause discontinuation, reason for discontinuation and withdrawal rates (Boosted file 3). Twelve (26%) of the reviews reported that they assessed acceptability using self-study measures, which included responses to hypothetical scenarios, satisfaction measures, attitudinal measures, reports of individuals on their perceptions of, and experiences with, the intervention, and opened-concluded interview questions (Additional file 4). None of the reviews specified a threshold criterion, i.eastward., the number of participants that needed to withdraw /discontinue treatment, for the intervention to exist considered unacceptable.

8 (19%) reviews assessed acceptability using both objective measures of behaviour and self-reported measures. These included two reviews measuring adherence and satisfaction [45, 46], three reviews focusing on dropout rates, take-upwards rates, reasons for discontinuation and a satisfaction measure out [47–49] one review combining the fourth dimension taken for wound healing aslope a measure of satisfaction and condolement [29], and two reviews using semi-structured interviews to explore participant experience of the intervention aslope intervention have-upward rates [50, 51].

We too extracted data on the time at which studies in each of the reviews assessed acceptability relative to the delivery of the intervention (Boosted file 5). 2 of the reviews (5%) assessed acceptability pre-intervention, which involved participants agreeing to take role in screening for a brief alcohol intervention [52] and willingness to participate in HIV self–testing [53]. Seven (16%) of the reviews assessed acceptability during the intervention delivery menstruation, while 17 (40%) assessed acceptability post-intervention. Fourteen reviews (33%) did not report when acceptability was measured, and in three (7%) of the reviews it was unclear when acceptability was measured. Inside these 3 reviews, it was unclear whether interpretations of intervention acceptability were based on anticipated (i.e. prospective) acceptability or experienced (i.eastward. concurrent or retrospective) acceptability.

Employ of theory

There was no mention of theory in relation to acceptability in any of these 43 reviews. None of the review authors proposed any link betwixt their definitions (when present) and assessments of acceptability and existing theory or theoretical models (i.e. scientific and citable theories/models). Moreover, none of the reviews proposed any link between implicit theories and their definitions and assessments of acceptability, or theory emerging during the studies reported in the systematic reviews. No links were proposed considering, by definition, an implicit theory is not articulated.

Definitions of acceptability: consensus group exercise

Extracted definitions of acceptability required a minimum of four of seven judges to endorse it as representing either an operational or conceptual definition. From the 29 extracts of text (phase 1 search results), the expert group identified 17 of the extracts as being operational definitions. Operational definitions included measureable factors such as dropout rates, all crusade discontinuation, treatment discontinuation and measures of satisfaction. Some reviews indicated that acceptability was measured according to a number of indicators, such equally effectiveness and side furnishings. The remaining 12 extracted definitions were non reliably classified as either operational or conceptual and were overlooked. For the fourteen extracted definitions based on the phase 2 search results, 2 endorsements (from three judges) was required for a definition to be considered as operational or conceptual. Seven definitions were considered operational definitions of acceptability, three definitions were identified as conceptual and 4 extracts were non reliably classified every bit either. Conceptual definitions included: "acceptability, or how the recipients of (or those delivering the intervention) perceive and react to it" ([49] p. two) "…patients reported being more willing to be involved" ([54] p. 2535) and "women were asked if they were well satisfied, unsatisfied or indifferent or had no response" with the intervention ([55] p. 504).

Study 2: Theoretical framework of acceptability

The process of identifying or writing explicit definitions for each of the proposed constructs in the theoretical framework of acceptability resulted in revisions to the TFA (v1) and the evolution of the revised TFA (v2) as we came to recognise inherent back-up and overlap. Figure 3 presents the TFA (v2) comprising seven component constructs.

The theoretical framework of acceptability (v2) comprising seven component constructs. Note: The seven component constructs are presented alphabetically with their predictable definitions. The extent to which they may cluster or influence each of the temporal assessments of acceptability is an empirical question

The inclusion of affective attitude equally a construct in the TFA (v2) is in line with the findings of the overview of reviews, in which measures of attitude take been used to assess acceptability of healthcare interventions. Affective attitude is divers equally "how an private feels about taking part in an intervention". The definition for burden was influenced by the Oxford dictionary definition, which defines burden every bit a "heavy load". We ascertain burden as "the perceived amount of effort that is required to participate in the intervention". The TFA construct of burden focuses on the burden associated with participating in the intervention (due east.one thousand. participation requires too much time or expense, or too much cerebral effort, indicating the burden is too great) rather than the individual'due south confidence in engaging in the intervention (see definition of self–efficacy below).

Opportunity costs are divers as "the extent to which benefits, profits, or values must be given up to engage in an intervention", taken from the health economics literature. Nosotros changed the construct label of "ethical consequences" to "ethicality", based on the Oxford dictionary definition of ethical, divers as "morally good or right". In the TFA (v2) ethicality is divers as "the extent to which the intervention has proficient fit with an private's value organization".

On reviewing the control items within the Illness Perception Questionnaire –Revised (IPQ-R), we realised all items focus on an individual'due south perceived control of the illness for example, "there is a lot I tin practice to control my symptoms" ([56], p. 5). These items did not reflect the construct of personal command as nosotros intended. We therefore considered how the relationship between conviction and personal control has been defined. Within the psychology literature the construct of self-efficacy has been defined in relation to confidence. Numerous authors have proposed that self-efficacy reflects confidence in the power to exert control over 1's own motivation, behaviour, and social environment [57]. We therefore considered a trunk of literature that groups control constructs together [38]. Self-efficacy is often operationalised as an individual's conviction in his or her capability of performing a behaviour [58, 59]. In TFA (v2) we ascertain the construct as "the participant's conviction that they can perform the behaviour(s) required to participate in the intervention".

The construct "intention" was removed from TFA (v2). This determination was taken upon a review of the extracted definitions of intention against our conceptual definition of acceptability. The Theory of Planned Behaviour [37] definition of intention states, "Intentions are assumed to capture the motivational factors that influence a behaviour; they are indications of how hard people are willing to try, of how much of an effort they are planning to exert, in order to perform the behaviour" ([37], p. 181). We propose that all other constructs within the TFA (v2) could be predictors of intention (due east.thousand. willingness to participate in an intervention). If acceptability (assessed by measuring the component constructs in the TFA) is proposed to be a predictor of intention (to engage in the intervention), to avoid circularity it is of import to retain a stardom between acceptability and intention.

We reviewed the definitions of the component constructs in TFA (v2) confronting our conceptual definition of acceptability to consider whether we were overlooking any important constructs that could farther enhance the framework of acceptability. Drawing on our knowledge of health psychology theory we discussed how perceptions of acceptability may be influenced by participants' and healthcare professionals' understanding of a healthcare intervention and how it works in relation to the problem information technology targets. As a outcome, we propose an additional construct that we labelled "intervention coherence". Our definition for this construct was informed by reviewing the affliction perceptions literature. Moss-Morris et al., divers "illness coherence" as "the extent to which a patient's illness representation provided a coherent understanding of the illness" (p. 2 [56]). Applying this definition within the TFA (v2), the construct of intervention coherence reflects an private'southward understanding of the perceived level of 'fit' between the components of the intervention and the intended aim of the intervention. We define intervention coherence equally "the extent to which the participant understands the intervention, and how the intervention works". Intervention coherence thus represents the confront validity of the intervention to the recipient or deliverer.

Next nosotros considered the applicability and relevance of the construct label "experience" for inclusion in the TFA (v2). Four of the constructs (affective attitude, brunt, opportunity costs and perceived effectiveness) could include a definition that referred to acceptability of the intervention as experienced (Additional file vi) (east.m. opportunity costs- the benefits, profits, or values that were given up to engage in the intervention) likewise equally a definition that referred to the intervention as anticipated (as defined in a higher place). In TFA (v1) 'experience' was being used to distinguish betwixt components of acceptability measured pre- or post-exposure to the intervention. In this sense experience is best understood as a characteristic of the assessment context rather than a singled-out construct in its own right. We therefore did not include 'experience' equally a dissever construct in the TFA (v2). However, the distinction betwixt predictable and experienced acceptability is a key characteristic of the TFA (v2). We propose that acceptability can be assessed from two temporal perspectives (i.e. prospective/ frontwards-looking; retrospective / backward-looking) and at iii unlike fourth dimension points in relation to the intervention commitment menstruation. The time points are (one) pre-intervention delivery (i.eastward. prior to any exposure to the intervention), (2) during intervention commitment (i.e. concurrent assessment of acceptability; when at that place has been some degree of exposure to the intervention and farther exposure is planned), and (3) mail-intervention delivery (i.eastward. post-obit completion of the intervention or at the end of the intervention delivery period when no further exposure is planned). This feature of the TFA is in line with the findings of the overview of reviews in which review authors had described the time at which acceptability was assessed every bit pre–intervention, during the intervention and post-intervention.

Discussion

We have presented the development of a theoretical framework of acceptability that tin be used to guide the cess of acceptability from the perspectives of intervention deliverers and recipients, prospectively and retrospectively. We propose that acceptability is a multi-faceted construct, represented by 7 component constructs: affective attitude, brunt, perceived effectiveness, ethicality, intervention coherence, opportunity costs, and self-efficacy.

Overview of reviews

To our knowledge, this overview represents the first systematic approach to identifying how the acceptability of healthcare interventions has been divers, theorised and assessed. Near definitions offered within the systematic reviews focused on operational definitions of acceptability. For instance, number of dropouts, handling discontinuation and other measurable variables such as side furnishings, satisfaction and uptake rates were used to infer the review authors' definitions of acceptability. Measures applied in the reviews were mainly measures of observed behaviour. Whilst the use of measures of observed behaviour does give an indication of how many participants initially hold to participate in a trial versus how many actually complete the intervention, oft reasons for discontinuation or withdrawal are not reported. There are several reasons why patients withdraw their participation that may or may not exist associated with acceptability of the intervention. For instance, a participant may believe the intervention itself is acceptable, notwithstanding they may undo with the intervention if they believe that the treatment has sufficiently ameliorated or cured their condition and is no longer required.

In the overview, merely eight of 43 reviews combined observed behavioural and self-study measures in their assessments of acceptability. A combination of self–study measures and observed behaviour measures applied together may provide a clearer evaluation of intervention acceptability.

The overview shows that acceptability has sometimes been confounded with the construct of satisfaction. This is evident from the reviews that claim to have assessed acceptability using measures of satisfaction. Yet, while satisfaction with a treatment or intervention tin can just be assessed retrospectively, acceptability of a treatment or intervention tin exist assessed either prospectively or retrospectively. We therefore propose that acceptability is unlike to satisfaction every bit individuals tin study (predictable) acceptability prior to engaging in an intervention. Nosotros argue that acceptability can be and should be assessed prior to engaging in an intervention.

There is evidence that acceptability can be assessed prior to engaging in an intervention [14]. Sidani and colleagues [fourteen] advise that there are several factors that can influence participants' perceptions of the acceptability of the intervention prior to participating in the intervention, which they refer to as treatment acceptability. Factors such equally participants' attitudes towards the intervention, ceremoniousness, suitability, convenience and perceived effectiveness of the intervention have been considered as indicators of treatment acceptability.

Theoretical framework of acceptability

The overview of reviews revealed no evidence of the development or application of theory as the basis for either operational or conceptual definitions of acceptability. This is surprising given that acceptability is not but an attribute of an intervention but is rather a subjective evaluation made by individuals who experience (or expect to experience) or deliver (or wait to deliver) an intervention. The results of the overview highlight the need for a clear, consensual definition of acceptability. Nosotros therefore sought to theorise the concept of acceptability in gild to empathise what acceptability is (or is proposed to be) and what its components are (or are proposed to be).

The distinction between prospective and retrospective acceptability is a key feature of the TFA, and cogitating of the overview of review results, which showed that acceptability has been assessed, before, during and after intervention delivery. We argue that prior to experiencing an intervention both patients and healthcare professionals can form judgements nearly whether they wait the intervention to be acceptable or unacceptable. These judgements may be based on the information provided about the intervention, or other factors outlined past Sidani et al., [fourteen] in their conceptualisation of handling acceptability. Assessment of anticipated acceptability prior to participation can highlight which aspects of the intervention could be modified to increment acceptability, and thus participation.

Researchers need to be clear nearly the purpose of acceptability assessments at different fourth dimension points (i.east. pre-, during or post-intervention) and the stated purpose should be aligned to the temporal perspective adopted (i.due east. prospective or retrospective acceptability). For example, when evaluating acceptability during the intervention delivery period (i.e. concurrent assessment) researchers have the selection of assessing the experienced acceptability up to this signal in fourth dimension or assessing the anticipated acceptability in the time to come. Different temporal perspectives alter the purpose of the acceptability assessment and may change the evaluation, due east.k. when assessed during the intervention delivery period an intervention that is initially difficult to adjust to may have low experienced acceptability merely high anticipated acceptability. Similarly post-intervention assessments of acceptability may focus on experienced acceptability based on participants' experience of the intervention from initiation through to completion, or on anticipated acceptability based on participants' views of what information technology would be similar to continue with the intervention on an on-going ground .(eastward.g. as part of routine care). These issues are outside the scope of this commodity but we will elaborate further in a split up publication presenting our measures of the TFA (v2) constructs.

Limitations

Although we take aimed to be systematic throughout the process, certain limitations should exist acknowledged. The overview of reviews included systematic review papers that claimed to assess the acceptability of an intervention. It is possible that some papers were not identified by the search strategy as some restrictions were put in identify to make the overview feasible. Nonetheless, the overview does provide a useful synthesis of how acceptability of healthcare interventions has been divers, assessed and theorised in systematic reviews of the effectiveness of healthcare interventions. In particular, the review highlights a singled-out need to advance acceptability research.

A key objective of this paper was to describe the procedures past which the TFA were developed. Frequently methods practical to theorising are not clearly articulated or reported within literature [31]. We have been transparent in reporting the methods we applied to develop the TFA. Our work in theorising the concept of acceptability follows the procedure outlined by Hox [33]. Withal, the theorising process was likewise iterative as we continuously reviewed the results from the overview of reviews when making revisions from TFA (v1) to TFA (v2). Nosotros carefully considered the constructs in both TFA (v1) and TFA (v2) and how they represented our conceptual definition of acceptability. We too relied on and applied our own noesis of health psychology theories in club to define the constructs. Given the big number of theories and models that comprise an even larger number of constructs that are potentially relevant to acceptability this deductive process should exist viewed as inevitably selective and therefore open to bias.

Implications: The use of the TFA

We propose the TFA will be helpful in assessing the acceptability of healthcare interventions within the evolution, piloting and feasibility, upshot and procedure evaluation and implementation phases described by the MRC guidance on circuitous interventions [1, 12]. Table iii outlines how the TFA can be applied qualitatively and quantitatively to assess acceptability in the different stages of the MRC intervention development and evaluation cycle.

The evolution stage of an intervention requires researchers to place or develop a theory of change (due east.g. what changes are expected and how they volition be achieved) and to model processes and outcomes (e.g. using analogue studies and other bear witness to place the specific outcomes and appropriate measures) [1]. Explicit consideration of the acceptability of the intervention, facilitated by the TFA, at this stage would assistance intervention designers make informed decisions virtually the form, content and delivery mode of the proposed intervention components.

The MRC framework suggests that acceptability should be assessed in the feasibility phase [1]. The TFA will aid intervention designers to operationalise this construct and guide the methods used to evaluate it, e.one thousand. by adapting a generic TFA questionnaire or an interview schedule that nosotros take developed (to be published separately). A pilot study often represents the starting time attempt to deliver the intervention and the TFA tin be used at this stage to decide whether anticipated acceptability, for deliverers and recipients of the intervention, corresponds to their experienced acceptability. Necessary changes to aspects of the intervention (e.g. if recruitment was lower or attrition higher than expected) could be considered in light of experienced acceptability.

In the context of a definitive randomised controlled trial the TFA can be applied within a process evaluation to assess anticipated and experienced acceptability of the intervention to people receiving and/or delivering the healthcare intervention at different stages of intervention delivery. Findings may provide insights into reasons for low participant retentivity and implications for the allegiance of both delivery and receipt of the intervention [60]. High rates of participant dropout in trials may exist associated with the brunt of participating in inquiry (eastward.grand. filling out long follow–up questionnaires) and practise not always reverberate problems with acceptability of the intervention under investigation [61, 62]. Insights nigh acceptability from process evaluations may inform the interpretation of trial findings (e.g. where the primary outcomes were not as expected, a TFA assessment may indicate whether this is attributable to low acceptability leading to low date, or an ineffective intervention).

The TFA can as well be applied to appraise acceptability in the implementation phase when an intervention is scaled-up for wider rollout in 'existent world' healthcare settings (e.g. patient engagement with a new service being offered as role of routine care).

Conclusion

The acceptability of healthcare interventions to intervention deliverers and recipients is an important issue to consider in the evolution, evaluation and implementation phases of healthcare interventions. The theoretical framework of acceptability is innovative and provides conceptually distinct constructs that are proposed to capture key dimensions of acceptability. Nosotros have used the framework to develop quantitative (questionnaire items) and qualitative (topic guide) instruments for assessing the acceptability of complex interventions [63] (to be published separately). We offer the proposed multi-construct Theoretical Framework of Acceptability to healthcare researchers, to accelerate the scientific discipline and practice of acceptability assessment for healthcare interventions.

References

-

MRC U. Developing and evaluating circuitous interventions: new guidance. London: Medical Enquiry Council; 2008.

-

Say RE, Thomson R. The importance of patient preferences in treatment decisions—challenges for doctors. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):542–five.

-

Torgerson D, Ryan M, Donaldson C. Effective Health Care bulletins: are they efficient? Qual Wellness Intendance. 1995;4(ane):48.

-

Diepeveen S, Ling T, Suhrcke Chiliad, Roland Grand, Marteau TM. Public acceptability of regime intervention to alter wellness-related behaviours: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):756.

-

Stok FM, de Ridder DT, de Vet E, Nureeva L, Luszczynska A, Wardle J, Gaspar T, de Wit JB. Hungry for an intervention? Adolescents' ratings of acceptability of eating-related intervention strategies. BMC Public Health. 2016;xvi(i):ane.

-

Fisher P, McCarney R, Hasford C, Vickers A. Evaluation of specific and non-specific effects in homeopathy: feasibility written report for a randomised trial. Homeopathy. 2006;95(four):215–22.

-

Hommel KA, Hente Eastward, Herzer K, Ingerski LM, Denson LA. Telehealth behavioral treatment for medication nonadherence: a pilot and feasibility study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(four):469.

-

Borrelli B, Sepinwall D, Ernst D, Bellg AJ, Czajkowski Southward, Breger R, DeFrancesco C, Levesque C, Sharp DL, Ogedegbe G. A new tool to appraise treatment fidelity and evaluation of treatment fidelity across 10 years of wellness behavior research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(v):852.

-

Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons K, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation inquiry in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and grooming challenges. Adm Policy Ment Wellness Ment Health Serv Res. 2009;36(1):24–34.

-

Medical Research Council (Britain), Health Services and Public Health Inquiry Board. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to ameliorate health. BMJ. 2000;321(7262):694–6.

-

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew Chiliad. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Quango guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

-

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond 50, Bonell C, Hardeman W, Moore L, O'Cathain A, Tinati T, Wight D. Procedure evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258.

-

Becker CB, Darius E, Schaumberg K. An analog study of patient preferences for exposure versus alternative treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(12):2861–73.

-

Sidani Southward, Epstein DR, Bootzin RR, Moritz P, Miranda J. Assessment of preferences for treatment: validation of a measure. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32(4):419.

-

Tarrier North, Liversidge T, Gregg L. The acceptability and preference for the psychological handling of PTSD. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(xi):1643–56.

-

Dillip A, Alba Southward, Mshana C, Hetzel MW, Lengeler C, Mayumana I, Schulze A, Mshinda H, Weiss MG, Obrist B. Acceptability–a neglected dimension of admission to health care: findings from a written report on childhood convulsions in rural Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):113.

-

DOLL R. Surveillance and monitoring. Int J Epidemiol. 1974;3(4):305–14.

-

Staniszewska Southward, Crowe S, Badenoch D, Edwards C, Barbarous J, Norman Due west. The Prime project: developing a patient evidence‐base. Health Expect. 2010;13(3):312–22.

-

Andrykowski MA, Manne SL. Are psychological interventions effective and accepted by cancer patients? I. Standards and levels of evidence. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32(2):93–seven.

-

Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. 1989.

-

Campbell M, Egan M, Lorenc T, Bond 50, Popham F, Fenton C, Benzeval Thou. Considering methodological options for reviews of theory: illustrated by a review of theories linking income and health. Syst Rev. 2014;3(i):1–eleven.

-

Davidoff F, Dixon-Forest G, Leviton Fifty, Michie S. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(3):228–38. doi:ten.1136/bmjqs-2014-003627.

-

Giles EL, Sniehotta FF, McColl Due east, Adams J. Acceptability of financial incentives and penalties for encouraging uptake of healthy behaviours: focus groups. BMC Public Wellness. 2015;15(1):one.

-

ICEBeRG. Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. 2006.

-

Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based? Evolution of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol. 2010;29(1):1.

-

Rimer BK, Glanz K. Theory at a glance: a guide for health promotion do. 2005.

-

Berlim MT, McGirr A, Van den Eynde F, Flake MPA, Giacobbe P. Effectiveness and acceptability of deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subgenual cingulate cortex for treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2014;159:31–8.

-

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti M, Geddes JR, Higgins JPT, Churchill R, Watanabe North, Nakagawa A, Omori IM, McGuire H, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:746–58.

-

Kedge EM. A systematic review to investigate the effectiveness and acceptability of interventions for moist desquamation in radiotherapy patients. Radiography. 2009;15:247–57.

-

Braun 5, Clarke V. Using thematic assay in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;iii(ii):77–101.

-

Carpiano RM, Daley DM. A guide and glossary on postpositivist theory building for population health. J Epidemiol Customs Wellness. 2006;60(7):564–70.

-

Epstein LH. Integrating theoretical approaches to promote physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15(4):257–65.

-

Hox JJ. From theoretical concept to survey question. 1997): Survey Measurement and Procedure Quality. New York ua: Wiley; 1997. p. 45–69.

-

Locke EA. Theory edifice, replication, and behavioral priming Where do we need to become from hither? Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(3):408–xiv.

-

Thompson JD. On Building an Authoritative Science. Adm Sci Q. 1956;ane(1):102–11.

-

Weick KE. Driblet Your Tools: An Allegory for Organizational Studies. Adm Sci Q. 1996;41(2):301–13.

-

Ajzen I. The theory of planned beliefs. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;l(two):179–211.

-

Michie South, Johnston One thousand, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus arroyo. Qual Saf Wellness Care. 2005;14(ane):26–33.

-

Higgins JPT, Green SP, Wiley Online Library EBS, Cochrane C, Wiley I. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken; Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

-

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(one):one–12.

-

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Group C. The Consort argument: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357(9263):1191–iv.

-

Atkins D, Eccles G, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Henry D, Loma S, Liberati A, O'Connell D, Oxman Advertizement, Phillips B. Systems for grading the quality of prove and the force of recommendations I: disquisitional appraisal of existing approaches The Form Working Group. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;four(1):38.

-

Armijo‐Olivo Due south, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparing of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Wellness Exercise Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;eighteen(1):12–eight.

-

Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, Atkins D, Preventive MWGTU, Forcefulness ST. Electric current methods of the United states of america Preventive Services Chore Force: a review of the procedure. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3):21–35.

-

Andrews M, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, McEvoy P, Titov N. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health intendance: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5(x):e13196.

-

Blenkinsopp A, Hassey A. Effectiveness and acceptability of customs pharmacy‐based interventions in type ii diabetes: a disquisitional review of intervention design, pharmacist and patient perspectives. Int J Pharm Pract. 2005;13(4):231–40.

-

Kulier R, Helmerhorst FM, Maitra N, Gülmezoglu AM. Effectiveness and acceptability of progestogens in combined oral contraceptives–a systematic review. Reprod Wellness. 2004;1(1):ane.

-

Kaltenthaler E, Sutcliffe P, Parry G, Rees A, Ferriter M. The acceptability to patients of computerized cognitive behaviour therapy for depression: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1521–xxx.

-

Brooke-Sumner C, Petersen I, Asher 50, Mall S, Egbe CO, Lund C. Systematic review of feasibility and acceptability of psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia in low and middle income countries. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:nineteen.

-

Muftin Z, Thompson AR. A systematic review of cocky-help for disfigurement: Effectiveness, usability, and acceptability. Trunk Paradigm. 2013;x(4):442–50.

-

El-Den S, O'Reilly CL, Chen TF. A systematic review on the acceptability of perinatal depression screening. J Affect Disord. 2015;188:284–303.

-

Littlejohn C. Does socio-economic status influence the acceptability of, attendance for, and outcome of, screening and cursory interventions for alcohol misuse: a review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:540–five.

-

Figueroa C, Johnson C, Verster A, Baggaley R. Attitudes and acceptability on HIV cocky-testing among primal populations: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2015;xix(11):1949–65.

-

Botella C, Serrano B, Baños RM, Garcia-Palacios A. Virtual reality exposure-based therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A review of its efficacy, the adequacy of the treatment protocol, and its acceptability. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2533–45.

-

Rodriguez MI, Gordon-Maclean C. The safety, efficacy and acceptability of task sharing tubal sterilization to midlevel providers: a systematic review. Contraception. 2014;89(6):504–eleven.

-

Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie K, Horne R, Cameron 50, Buick D. The revised affliction perception questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychol Wellness. 2002;17(1):1–16.

-

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral alter. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191.

-

Lee C, Bobko P. Self-efficacy beliefs: comparison of v measures. J Appl Psychol. 1994;79(3):364.

-

Cloudless South. The self‐efficacy expectations and occupational preferences of females and males. J Occup Psychol. 1987;60(3):257–65.

-

Rixon L, Baron J, McGale North, Lorencatto F, Francis J, Davies A. Methods used to accost fidelity of receipt in health intervention research: a citation analysis and systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:ane.

-

Eborall HC, Stewart MCW, Cunningham-Burley S, Cost JF, Fowkes FGR. Accrual and drib out in a primary prevention randomised controlled trial: qualitative study. Trials. 2011;12(1):seven.

-

Sanders C, Rogers A, Bowen R, Bower P, Hirani SP, Cartwright M, Fitzpatrick R, Knapp M, Barlow J, Hendy J, et al. Exploring barriers to participation and adoption of telehealth and telecare within the Whole Organisation Demonstrator trial: a qualitative study. 2012.

-

Wickwar S, McBain H, Newman SP, Hirani SP, Hurt C, Dunlop Northward, Overflowing C, Ezra DG. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a patient-initiated botulinum toxin treatment model for blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm compared to standard care: written report protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17(i):1.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. The BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

-

APA. Glossary of Psychological Terms. 2017 [online] Available at: http://www.apa.org/research/activeness/glossary.aspx?tab=3. [Accessed xix Jan 2017].

-

Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Non applicable.

Availability of data and material

Data will be available via the supplementary files and on request past e-mailing the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JF and MC conceived the study and supervised this work. MS conducted the overview of reviews and wrote the main torso of the manuscript. MC completed reliability checks on the screening of citations and 10% of the full texts included in the overview of reviews. MC besides contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. JF completed reliability checks on 10% of the total texts included in the overview of reviews. JF also contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. All 3 authors contributed intellectually to the theorising and development of the theoretical framework of acceptability. All authors canonical the final version of the manuscript (manuscript file).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Non applicable to this report.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable to this study.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Systematic review filters. Description of data: List of each review filter applied to MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO. (DOCX xix kb)

Additional file two:

References. Clarification of information: Citation details of all the systematic reviews included in the overview of reviews. (DOCX 40 kb)

Additional file 3:

Behavioural assessments of acceptability. Description of data: How acceptability was assessed in the included systematic reviews based on measures of observed behaviour. (DOCX 12 kb)

Additional file 4:

Cocky study assessments of acceptability. Description of information: Summary of the self-report measures of acceptability reported in the overview of reviews. (DOCX 12 kb)

Additional file v:

When was acceptability assessed?. Description of data: Summary of the timing of acceptability assessments relative to get-go of intervention reported in the papers identified in the systematic reviews. (DOCX 12 kb)

Additional file vi:

Definition of TFA component constructs. Description of information: Definitions of each of the seven component constructs, including predictable acceptability and experienced acceptability definitions for applicable constructs. (DOCX 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilise, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you lot give appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/naught/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this article

Sekhon, M., Cartwright, M. & Francis, J.J. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res 17, 88 (2017). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

Keywords

- Acceptability

- Defining constructs

- Theory development

- Circuitous intervention

- Healthcare intervention

Source: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

0 Response to "is the extent to which an operational definition measures what it is intended to measure"

Post a Comment